Nurturing Relational Connections Across Boston's Christian Community

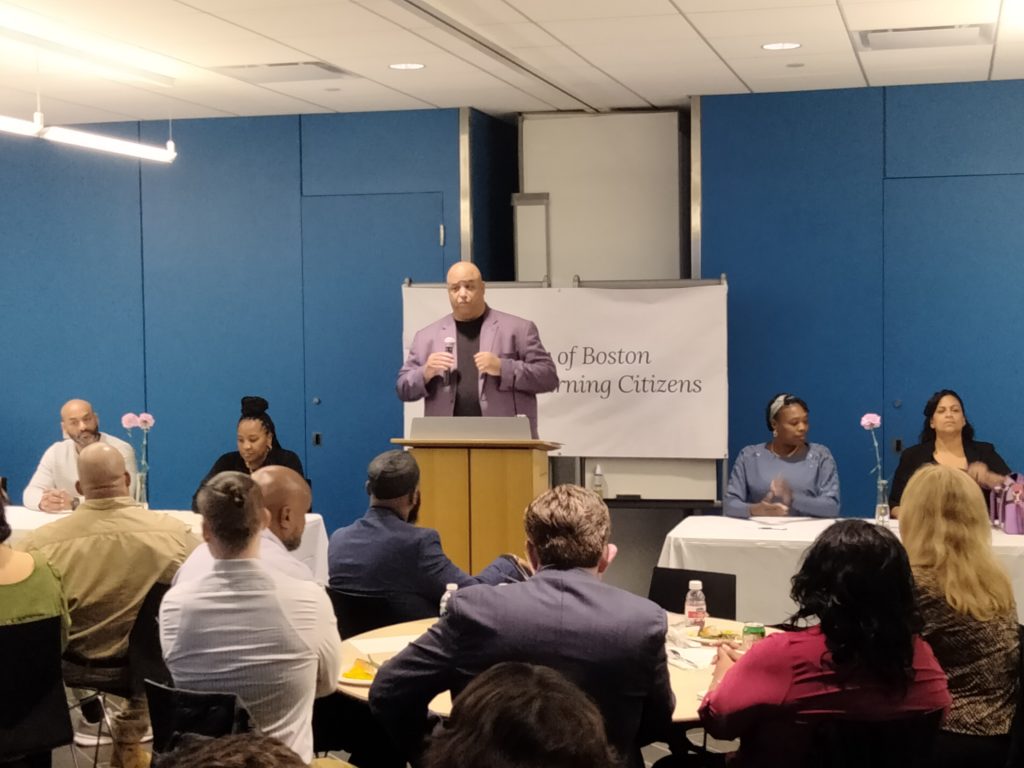

In these weeks leading up to Boston Flourish on November 10, we’re featuring the organizations that will be presenting at the conference. This week, we’re featuring the City of Boston’s Office of Returning Citizens. We had the chance to learn more about this ministry from the director of this office David Mayo – Read below to hear about what led him to this work and how they serve returning citizens in our city!

Can you tell us a little bit about your background and your interest in working with returning citizens?

I grew up in a family of five with a single mother in an inner city community of neighborhood crews and gangs in New York City. I then became a “Fatherless Son” and spent five years as a foster child in the New York Child/Family Services system. This led me to have an interest in working with returning citizens, which I began in 2014 as a youthful Parole and Reentry Officer. I felt drawn here by God and the greater opportunity to work with incarcerated young men.

Wow, that’s fascinating. Can you share more about your church background?

I was introduced to church when I was 13 by my Great-Grandmother and found my love for God in the choir. I gave my life to Christ in June of 1990 and was called to preach six months later. I now have over thirty years of ministerial experience, having planted two churches and served as founding and senior pastor of congregations in Northern Virginia and South Carolina.

Can you share about how you serve and support returning citizens in your office?

I have had the privilege of serving in this role for the past three months and it is my job goal to engage, equip and to empower the 3000+ returning citizens of Boston with the tools to create and advocate for their independence and stability in restoring their lives. The Returning Citizen process to reentry begins about 90 days before release in setting up a reentry plan and and discussing next steps. Upon release, we connect returning citizens to resources and programs in the community and monitor their transition with case managers.

What are you hoping to come out of the gathering on November 10?

I’d love to come away with new partners who are passionate and committed to restoring the lives of returning citizens.

Can you share a story about the impact of your work?

We recently had a gentleman who was released into a halfway house. He had no ID, no family, no support and we were able to get him into a housing program. You can also watch Arlis Evans’ story below.

What is a resource that everyone should know about?

Our website has a great list of resources that are available for returning citizens – everything from birth certificates, to housing and health services, to transportation and food resources. I wish that everyone knew about it so they can help people they know in the process of reentering back into life in Boston.

What does it mean to you to see Boston Flourish?

Seeing Boston Flourish means the destruction of stereotypes and silos for the purpose of unity and the influence of the kingdom of God in the earth. If we seize the moment of this opportunity to walk in the kingdom principles that God offers to us, we have the possibility to affect change, not only in the lives of the Boston community but in the earth completely! Selah!

“My dream is that Christians throughout the city would lock arm in arm, seeing the Melnea Cass area as a mission field to push back darkness, turning Methodone Mile to Miracle Mile, one soul at a time.”

Pastor Sam Acevedo

In these weeks leading up to Boston Flourish on November 10, we’re featuring the organizations that will be presenting at the conference. This week, we’re featuring Miracle Mile Ministries, a long-standing inter-church initiative that is making an impact in powerful ways. We had the chance to learn more about this ministry from Pastor Sam Acevedo – Read below to hear about the transformation they are seeing take place through their ministry!

Tell us a little bit about Miracle Mile Ministries?

Miracle Mile Ministries is a collaborative of churches devoted to a sustained, deliberate, strategic response to the area we call “Miracle Mile,” a roughly 2-square-mile area in the South End of Boston often referred to as “Mass & Cass” or “Methadone Mile.” It is led by a core group of six Boston-area Lead Churches (Congregación León de Judá, Antioch Community Church Brighton, Cornerstone Church, Restoration City Church, Hilltop Church and Symphony Church) and also involves a dozen or so churches and parachurch ministries from throughout Boston’s neighboring communities who faithfully support this effort, week after week.

Wow, that’s really awesome to hear. Can you tell us about this ministry began?

This ministry began in 2012 as a weekly sidewalk outreach on Saturday mornings at of Congregación León de Judá , serving coffee and making friends with people in the neighborhood around the church who were enduring homelessness and other needs. In 2014, “the breakfast” moved into Lion of Judah’s basement fellowship hall, allowing the church to serve a fuller breakfast, year-round, and conduct an evangelistic service. Over time, volunteers from area churches and ministries would flock to the “breakfast,” and today there are dozens of volunteers who contribute to make this ministry happen on a weekly basis.

Over the last 10 years, every Saturday morning – whether amid a snowstorm or on Christmas Day – Miracle Mile Ministries has had the privilege of feeding and clothing anywhere from 60 to 100 guests each week, who come to us from the neighboring streets and surrounding shelters. With the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Miracle Mile volunteers have provided 100 sidewalk “to go” breakfasts and clothing each week, as well direct interaction with our neighbors at Rosie’s and the tent-dwellers on Atkinson Street’s tent encampment. That is nearly 800 guests each year – many of them struggling with the ravishes of substance abuse addiction, working hard on coming clean, getting on their feet, and achieving their destiny.

What is the current state of the situation?

Never has the crisis of homelessness and addiction in Boston been more stark, and never has the need for Miracle Mile Ministries been more ardent. Perhaps the worst expression of Boston’s homelessness crisis has been the “Mass & Cass” tent encampment – located only a couple of blocks from the Congregación León de Judá – that at its darkest, according to a City of Boston survey, included 70 to 90 tents sheltering an estimated 143 human beings. Most of the tent dwellers reported widespread drug use (87% use cocaine or crack cocaine, 76% use opiates, 20% methamphetamines (1).

What is the approach you take to serve those struggling with addiction?

First, we seek to meet immediate needs, as Jesus asks his followers to do in Matthew 25: “For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me . . .” (Matthew 25:35-36). Since the pandemic, we set up tables out on the street to serve our guests a hot breakfast and hot coffee or tea. Many times they form a single line that often reached from our door around the corner to the door of our neighbor, Rosie’s Place. On that street, we formed a “conveyor belt of love,” giving our guests food, as well as clothing.

Then we introduce our guests to the gospel and its transforming power through outdoor piano worship (including in the sleet and rain) and a street corner “Prayer Booth.” It has a sign that reads “Prayer here!” and we minister in the open air to our Guests – and in fact, to any passersby. When we visit the Mass & Cass area, we move from tent to tent with care packages and in and invite those we encountere to receive prayer – including to invite Jesus into their lives. Many of them have. And several have made their way to our mid-week Bible Studies specific to those experiencing addiction and homelessness.

What transformation have you seen take place?

The ultimate goal of Miracle Mile Ministries is to see many of our Guests – even if not all – take their first solid steps toward a life free of despair and the bondage of addiction. As other Miracle Mile volunteers hand out care packages, recovery specialists also arrive armed with resource binders ready to refer anyone who is ready for a change to community services such as detox and rehab facilities, transitional housing, or employment. Between June of 2020 and July of 2021, our Together Initiative workers made 591 follow-up calls to 64 Guests. Our volunteers have also driven Guests to detox and rehab facilities as far away as Worcester. More than half of them have either received their own apartments or are in transitional housing. Roughly two-thirds (62%) have been clean – free of illicit drug or alcohol use – for at least year. Others have successfully completed a residential treatment program.

For many of our Guests, their first steps to transformation also involves church attendance. A recent survey identified at least 36 men and women drawn from the Miracle Mile community who have attended services at Lion of Judah more than once over the last 18 months. An average of 5 to 10 Guests attend either our Tuesday night Bible Study or our weekly Wednesday morning Bible Study (dubbed, “the Freedom Group”). In fact, in 2019, Lion of Judah’s last open air baptisms, 10 of our Guests – the limit of our bus – were baptized into the faith. These are many of the ways that our Guests are beginning a new life of freedom.

I’d encourage you to watch Jerome’s story below. In the three years since Jerome first came to Miracle Mile, Jerome has moved into his own one-bedroom apartment, he recently celebrated his first Christmas with his family in 45 years, and has become an indispensable member of the Miracle Mile Team. “If I can change in the 60-something years I was doing alcohol and drugs, trust me you can change, too.”

What is your dream for your ministry? How can Christians in Boston come alongside your efforts?

My dream is to see the Church rise up as a synchronized unit to confront the forces of darkness now known as Methodone Mile / Mass & Cass. At this point, we need ownership and infrastructure to shift a longstanding voluntary fellowship of churches around Boston’s homelessness and opioid crisis, into a formal, functioning multi-church organization. Volunteers are needed for everything from organizing supplies, to running bible studies, to picking up and sorting donated food, to picking up needles and trash, to engaging people on the street and meeting guests, to committed prayer. There are times we have to pick and choose whether we do one thing or another and more hands on deck is absolutely necessary for us to have the impact we want to have. My dream is that Christians throughout the city would lock arm in arm, seeing the this as a mission field to push back darkness, turning Methodone Mile to Miracle Mile, one soul at a time.

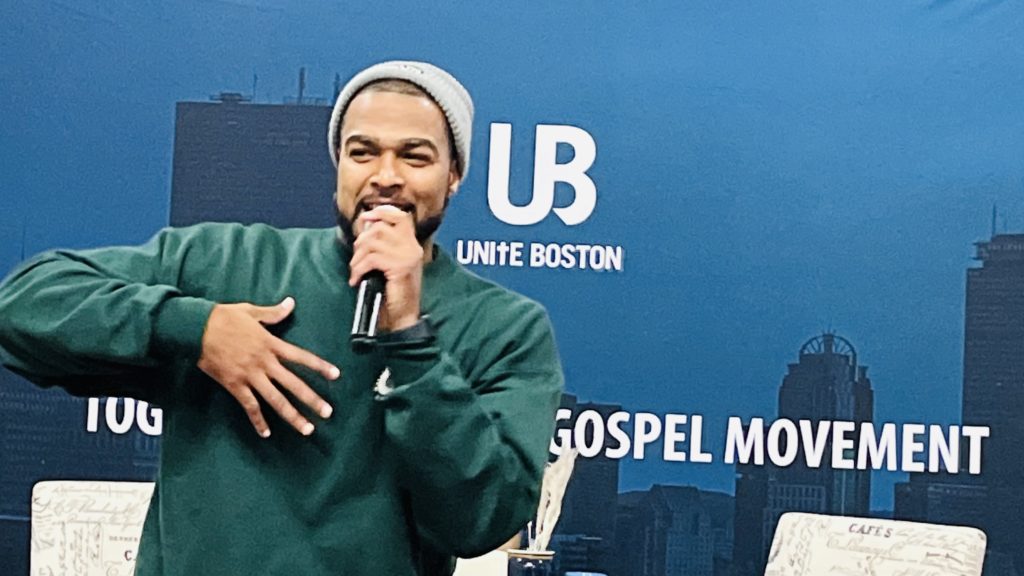

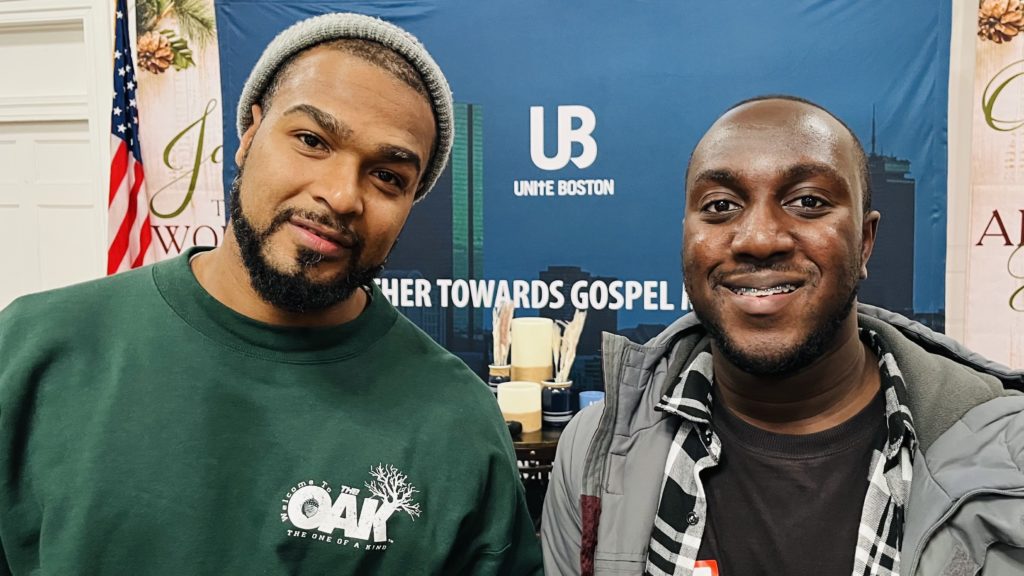

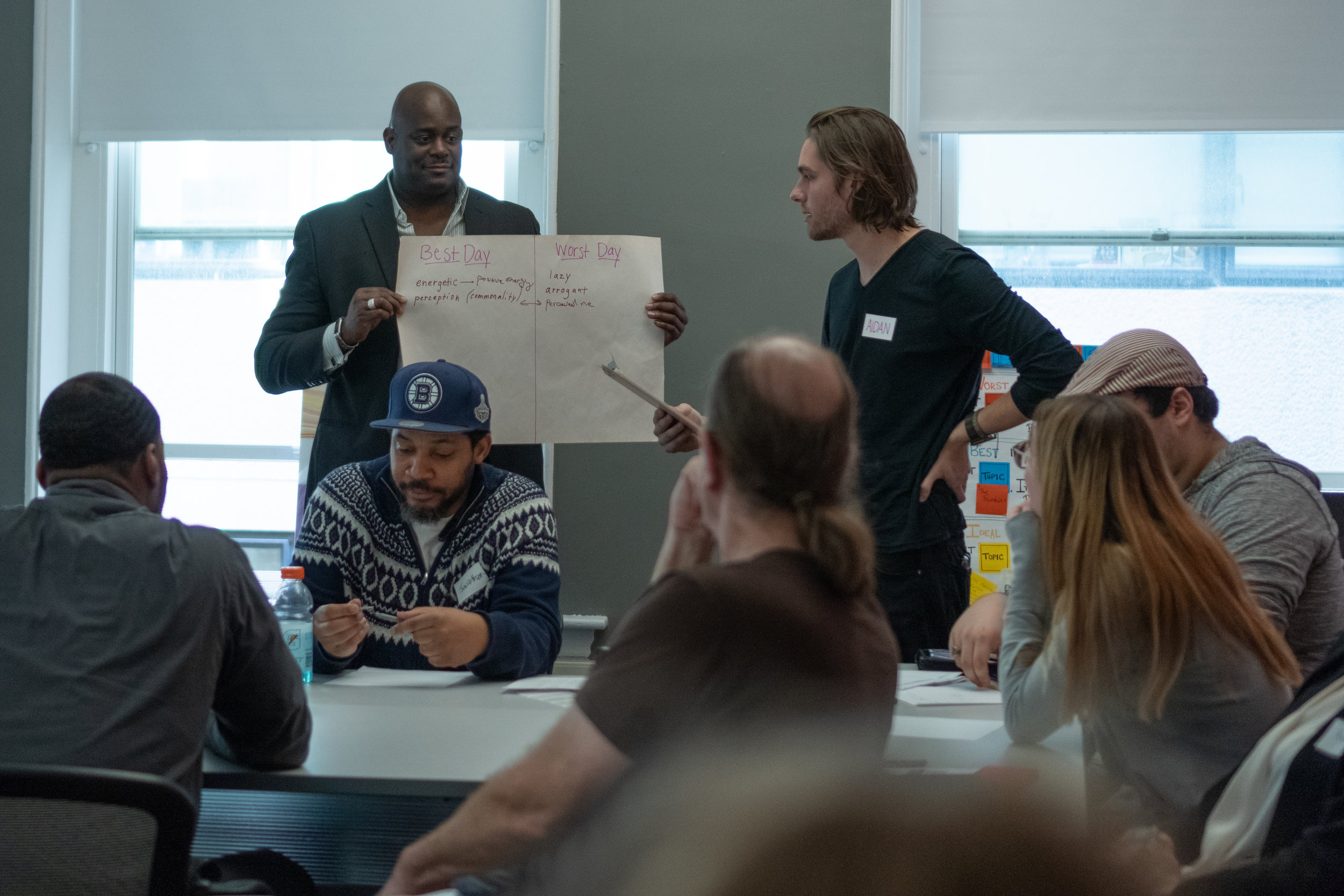

It was awesome! After a 2-year hiatus, UniteBoston’s 2022 worship concert brought us “together again” to worship Jesus in the heart of Boston. There were 15 different organizations hosting ministry tables surrounding the perimeter of the gathering, 30+ members of a community choir, and hundreds of attendees and passersby who stopped by for a portion of the evening to listen to the music, learn about the various organizations in the city, or receive prayer.

Read on to see photos and read personal testimonies about the impact of this gathering! You can also click on this link to follow the artists on their media platforms click here to listen to the playlist for the concert on Youtube!

All Photos by Rosa Caban

“I really enjoyed the worship and fellowship during “together again”. A highlight of my night was making new friends and praying for a young couple after finishing my set. It’s nice to not just attend a church but take nights like these to go out into the city and be the church… we never know when we’ll meet someone who needs an encounter with the love of Jesus. Thanks Unite Boston, donors, and all those involved in putting this together.” – Ada Betsabe

“It was great to see so many other artists in Boston that are excited about Jesus. It doesn’t always feel that way, so I’m incredibly grateful for the reminder.” – Doully Yang

“One of the things I enjoy about doing music is the opportunity to collaborate. And the UB concert vision really embodied that spirit. It was so encouraging to be a part of an event where Christian artists and musicians supported each other in the heart of worship!” – Caleb McCoy

This year, we brought together the community and had the opportunity to make room for ministries from across the city to share their mission with the city.

There were a lot of great moments of togetherness:

We also had the pleasure of building a community choir that brought together members from Gordon College God’s Chosen Gospel Choir and members of the community who have a passion for worshipping God.

“It was a beautiful glimpse into the true Body of Christ as we worshipped together. I was especially moved by the Gospel Youth Choir and their fervor for Jesus. And to think that we were right down there at the Boston Harbor proclaiming Jesus!”

-Pastor Richard Rhodes, Grace Chapel

Alexis Monroe and Kika Ghobrial were the MCs for the event and Grain of Wheat Christian ministries brought their musical gifts during the program intermission.

Other testimonies:

“I was visiting from Chicago this weekend and happened upon the choir. It was such a blessing. We were on the way to dinner without reservations. Thankfully we were able to circle back while we waited. May God continue to bless your ministry!” – @acalhy

“My favorite moment was with the lemonade stand owner which was adjacent to where we were setting up. I told him that today is going to be a great day for his business. He said that even when they have concerts here, he doesn’t make any money. I responded, “Today will be different – it’s a different vibe.” He said, “I hope so.” Later I ran into him and told him to make me a lemonade. When I came back to get it, he said, “Oh shoot, I forgot to make yours cause right after you ordered yours, I got so busy with customer after customer. You brought me luck!” I said, “No, God did it.” and he said “Yes he did!” This was a great chance to testify about God to many people who don’t normally go to church!” -Emmanuel Nicolas

“During one of the songs I see an older couple walk across the lawn near us checking things out. They look like tourists from Texas – 2 white people, mid-50s, too nicely dressed for this event. I remember thinking that they looked out of place. Then the man threw both of his hands up in worship and the woman started dancing. They participated until the end and we talked with them briefly after. They are from Texas and are spending a few days in Boston as part of a broader New England vacation. They just stumbled across the event and were excited to see Christian life in Boston. Their son lives in the burbs and hasn’t found a church community, and they didn’t think there was any life here. They were very encouraged by what they saw!” -Jeff Bass, Executive Director, Emmanuel Gospel Center

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the event and our fundraising goals. Thanks to each of you for being part of the UB community – it is a joy to serve alongside each of you, as together we seek greater gospel movement in our city!

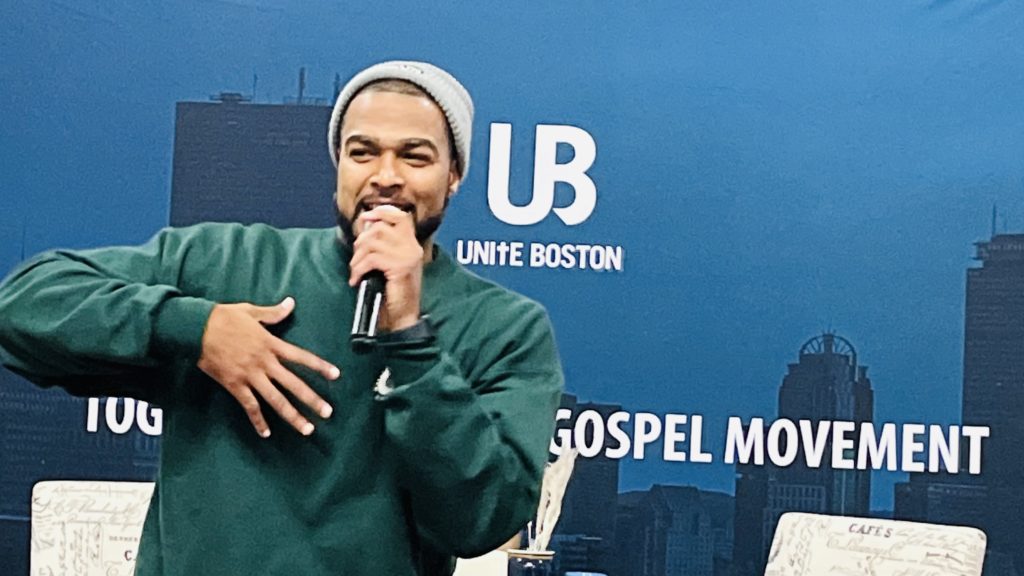

“Together Again” is UniteBoston’s first big concert since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Taking place on September 17th in downtown Boston, this concert is the opportunity for Christians to come together in a public place to worship.

We have an incredible line-up of Boston-based artists who are performing – Meet them below to hear why they are excited about the concert, and find links to follow them on their media platforms!

You can also hear a little bit about the concert and the music being performed by Jalen Williams and Jen Aldana from this Instagram Live session that took place on Friday.

Jen Aldana

Doully Yang

Caleb McCoy

Ada Betsabe

Jalen Williams

Join us to support Boston-based artists and to hear great jams that are glorifying God filling the heart of the city!