To Commemorate Migrant Sunday, we are sharing a blog that is written by local author and theologian Daniel Montañez. Daniel is founder and director of Mygration Christian Conference, a PhD student at Boston University School of Theology, and the coeditor of “The Church and Migration: A Theological Vision for the People of God.” Read below to hear Daniel share about the Christian ethic of bridge-building based out of Ephesians 2.

What are the walls of hostility we erect to exclude our immigrant neighbors? Walls can be physical, such as the 1,954-mile wall along the US-Mexico border. Hard and heavy walls made of bricks, metals, wires, and wood represent a division between people, culture, and national citizenry. Walls can also be mental or emotional, often resulting from difference in thought or feelings of fear toward those whom one may disagree with or not understand. In this way, walls can serve as a means of self-preservation and protection from the “other.” Finally, walls can be spiritual, as all too often Christians have excluded those who hold differing beliefs and convictions on religious matters. There is no shortage of reasons that feed the human proclivity to build walls; however, there are several reasons Christians are called to rise above the walls we build.

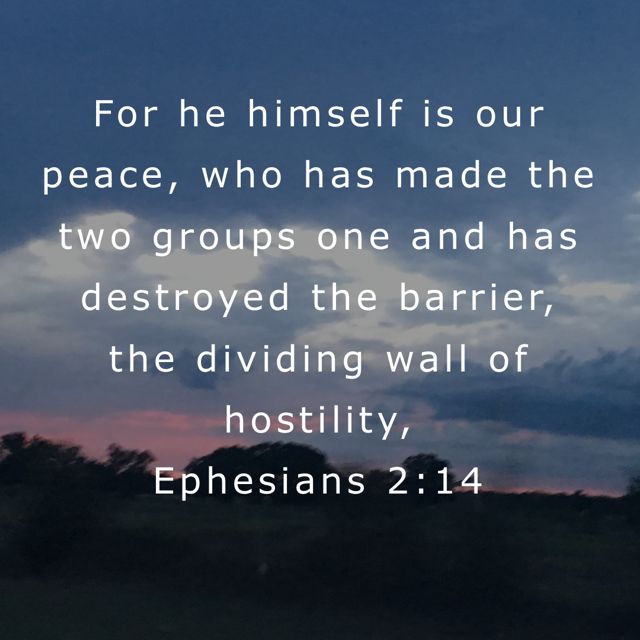

The book of Ephesians introduces us to a Christian ethic of bridge-building. In chapter 2, verses 14–18, Paul writes,

“For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to create in himself one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility. He came and preached peace to you who were far away and peace to those who were near. For through him we both have access to the Father by one Spirit.”

The two groups Paul describes are Jewish and Gentile believers. There was much hostility between these two people groups in the Old Testament, as the Jews were considered God’s chosen people, according to the covenant relationship established with the nation of Israel. The practice of circumcision served as a physical sign of Israel’s covenant relationship with God and operated as a means of citizenship into the Israelite community and inheritance of God’s promises. Because the Gentiles were uncircumcised, they did not belong to the covenant community, as they were, as Paul describes, “without hope and without God in the world” (Eph 2:12).

However, while the Gentiles were not included within the promises of the Mosaic covenant, this is not to say that God was not at work building bridges between Jews and Gentiles in the Old Testament. The Greek word for Gentiles is “ethnos,” meaning nation or people. It is within the Abrahamic covenant that God promises to Abraham that “through your offspring all nations on earth will be blessed,” (Gen 22:18), signaling the coming together of Jews and Gentiles through a messianic figure from Israel. Jesus Christ is the fulfillment of this messianic promise and the one who builds bridges between Jews and Gentiles, establishing a model and an ethic for Christian living.

Many biblical scholars believe the wall Paul was referring to in this passage was “the Mosaic law itself with its detailed holiness code.” It served as an ideological fence around Israel, keeping outsiders and foreigners from participating in the social, cultural, and religious life of the community. The crucifixion of Christ served to destroy the wall that separated Jews and Gentiles from fellowship with one another. Furthermore, Christ’s sacrifice on the cross served as the atonement for humanity’s sins and the restoration of their relationship with God the Father. For this reason, it can be stated that Jesus Christ did not come to build a wall, but a bridge between God and humanity, and between Jews and Gentiles. It was a project so costly that only the riches of heaven could pay for this bridge through Christ’s blood on the cross.

What, then, are the implications of a Christian ethic of bridge-building for our world today? First, it calls us to move from an ethic of exclusion to embrace. In “The Church and Migration: A Theological Vision for the People of God, which I coedited with Wilmer EstradaCarrasquillo, Estrada-Carrasquillo posits an ethic of hospitality as a necessary component for embracing our immigrant neighbors. He writes, “Hospitality to migrant communities can take many shapes and forms. But to serve them well, we must look beyond the surface. We must make a concerted effort to know them and develop intentional relationships.” It is only by embracing an ethic of encounter with our immigrant neighbors that we discover the common ground on which we stand, and the prospect of embracing one another as members of the kin-dom of God.

Second, a Christian ethic of bridgebuilding calls us to move from a mindset of scarcity to opportunity. All too often we hear negative rhetoric of immigrants stealing American jobs and the economic burden immigrants have on the US economy. While these claims are often unsubstantiated, what is frequently overlooked is the revitalization immigrants are bringing to the life of the church. The Latino immigrant church, for example, is rapidly growing in the United States, buoyed by a Hispanic population that is expected to grow to 110 million by 2060.

Carolyn Dirksen argues, “If the American Church can embrace their spiritual brothers and sisters in this great migration, they will reaffirm their commitments to Christ and invite a kind of rejuvenation the Church has seldom seen.” To move from scarcity to opportunity means to believe that not only are there enough materials for building bridges, but that we can also partner in the work of building a better future together.

Finally, a Christian ethic of bridge building demands that Christians move from a place of fear to faith. According to Alejandra Guajardo-Hodge, “Fear may be a natural response to these modern-day challenges but is not the response that God demands of us. Love is the only way to face the challenge of the shifting world in God-honoring ways.” To choose faith over fear means to tear down the hostile walls of partisan politics that divide our nation, and to cast a new vision for the role of the church in the public square—“not to further exacerbate the problems of this world, but to become a part of the solution,” as we write in The Church and Migration.

The social ethic that Christ sets before us is a call to embrace the opportunity by faith to tear down the walls of hostility that divide us from our neighbors and to build bridges toward a holistic vision of peace, justice, and the flourishing of all humankind.

This article was originally published in the Boston University School of Theology 2023 Magazine entitled “Reaching Across.” You can also check out Daniel Montanez’ book “The Church and Migration,” which serves as an accessible and educational guide for pastors, church leaders, and parishioners to better understand what the Bible says about God’s heart towards people on the move and how these truths can be applied in our modern world. It is available for purchase in English and Spanish.