“Poking holes in one another’s theologies is easy; what is difficult is looking at someone who thinks about God in a completely different way than I do and finding a way to see its loveliness.”

This week’s blog is written by Elizabeth M. Smith, Ph.D. Elizabeth works as a pastoral associate at Holy Family Parish in Concord and is a Catholic systematic theologian and ecumenist in the Boston area. She received her doctorate from Catholic University in 2017, and also holds a Master of Philosophy, a Master of Divinity, and a Master of Sacred Music. In this blog, she describes the journey that God has led her through in her understanding of the work towards Christian unity.

I never liked the idea of practicing theology as an exercise in calling out those who don’t get it, or emphasizing those who aren’t in the club. My experience with fellow Christians in grad school was, unfortunately, often just such an exercise. Hoping to be aspiring apologists, I believe, I witnessed many well-intentioned Christians from various denominations in the DC area try to poke holes in one another’s theology and in one another’s traditions. These discussions – most of which were outside the classroom – always seemed to leave participants frustrated and drained. If we know a tree by its fruits, I was hopeful that I could find another tree.

I’ve always felt like a peacemaker. I feel more at home finding ways to describe similarities than confronting difference. More at home highlighting ways our differences complement each other rather than ways they separate us. I’m learning that the term for this is “receptive ecumenism.”

I felt the Holy Spirit create in me a deep desire to construct conversations that ran counter to the apologetics I heard in DC. While apologetics is a praiseworthy field, the movement of the Spirit doesn’t seem to reside in apologetics the way it did in the early centuries of the Church. The days of sorting out heretical positions have yielded, in my view, to a new age in which the Spirit beckons us to stop weeding, lest we uproot the entire garden.

I moved from DC to Boston in 2014, the time I began to write my doctoral dissertation. Although my major area up until this point was theology of God (mainly Trinitarian theology), I felt a strong move within myself pulling me toward ecumenism. As much as I loved pouring over the various views that theologians asked us to consider about who and what God is, I felt the Spirit telling me, “You’ve spent so much time trying to understand me, but do you understand you?” By “you,” in this case, I felt God meant “the entire Christian Church.” I spent years of my life discussing various understandings of God with other Christians, but I realized the conclusions didn’t matter if they divided Christians rather than united them. If our Christian theology draws us further from, instead of closer to, the maxim “they’ll know we are Christians by our love,” then it may be theology, but it isn’t all that Christian.

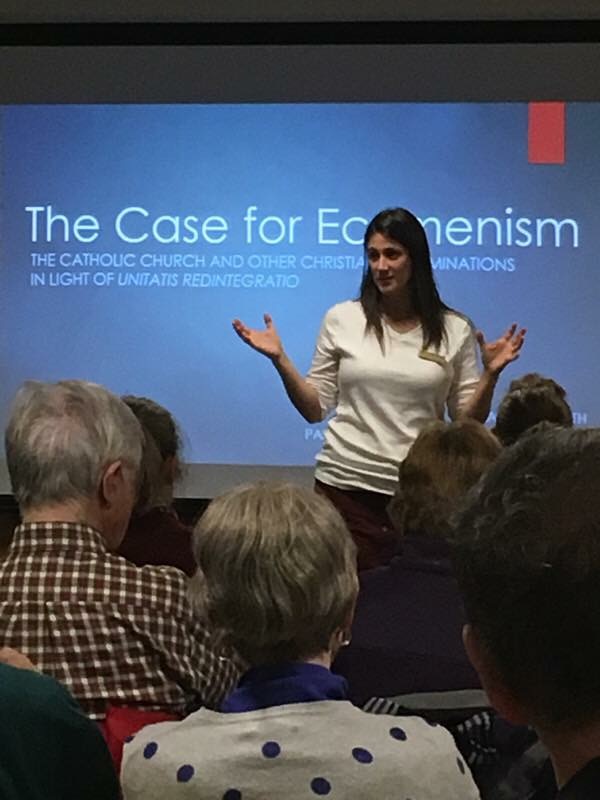

My dissertation seemed to pour out of me when I approached it as a reconciling tool rather than yet another exercise in making distinctions that divide. After graduating, I turned much of my paper into articles and a book. The Spirit seems to be working in the hearts of so many people I’ve encountered, because I’ve been invited to speak on my topic – mainly Anglican-Lutheran dialogues and their ecumenical successes in the US, Canada, and Northern Europe – in Louisiana, Minneapolis, Boston, and hopefully more. I know that our hearts are hungry for God, and if anyone is finding something attractive in my work, it isn’t of me; rather, it’s the Spirit of love that is of God, and I’m fortunate enough to be tapping into it as an ecumenist. That’s what people are attracted to, and I find that the more I open myself to it, the more opportunities keep springing up for me to do ecumenical work.

Poking holes in one another’s theologies is easy; what is difficult is looking at someone who thinks about God in a completely different way than I do and finding a way to see its loveliness. We are all unlovely in some way; yet, Christ died for all of us. What I’m learning in my work as an ecumenist is that the heart of Christian theology is to love the unlovely as Christ does, loving it into loveliness: “My song is love unknown; my saviors love to me. Love to the loveless shown, that they might lovely be.” We are all unlovely in some way, yet wholly lovable. The same is true for our theologies. This may sound like a watered down version of merely feel-good extractions from the cross of Christ; it is, in fact, the cross itself.

I’m attempting to argue this point as a theologian and scholar. I’m continually working to adopt it as a way of life, as well. I’m thankful to those in my ecumenical cohort and to Unite Boston for helping me move towards that goal.

Enjoyed reading this. Good work articulating the Spirit’s promptings in your heart, and acting on them.

Elizabeth Smith embodies my hope for future generations who will embrace all that we hold in common as children of God and draw us closer. I am both proud and blessed to have known her for years. I believe she speaks for many of her generation who view themselves as “spiritual” but not necessarily “religious”. Elizabeth clearly recognizes their hunger to align themselves with similar souls who share a common desire to love and serve God.